3.4 At last, Rome

Upon arriving in Rome in September 1838, Van Eycken and his companions never anticipated discovering anything tangible related to their mentor Navez, who had roamed the city’s streets decades earlier. However, they came across an inscription on a stone at the Passionist monastery on top of Monte Cavo, overlooking Rome: ‘there, we discovered with great enthusiasm the inscription “F. Navez 1819”, realising that, twenty years later, your students had written their own names on the very same wall. We also noticed the name of the renowned painter Gros [Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835)].’1 Although this inscription was the only physical link of Navez in Rome, his impact was far greater. Through correspondence, he continued to mentor the students and used his established social connections to provide support.

Most of the students spent their days to socializing and immersing themselves in the vibrant atmosphere at places like Caffè Greco,2 where they not only enjoyed coffee but by frequenting these spots engaged in social activities that shaped their (professional) identities. They also met their peers in the Vatican, where they, like many artists, sought and received permission to study and replicate artworks during designated time slots. While multiple artists worked there concurrently, none could use the Vatican as a permanent base or workshop, reflecting a broader trend in Rome where access to major art venues was tightly controlled. Roberti explains in one of his letters that he divides his time in Rome between the Vatican and painting from models in academies. And even after the closing hours of the Vatican, the students continued practicing their skills in an academy they established themselves. How this mini academy operated in practice remains unclear.

'I leave the Vatican only to paint from life, as the models here are of remarkable beauty. For the past month, we have been doing so, since the rainy season keeps us indoors. We are working as much as possible, dear Master, and in the evenings we draw together at an academy we have established ourselves.'3

In addition to encountering Italian High Renaissance masterpieces – the three were particularly drawn to Italian masters as Rafaël (1483-1520) and Michelangelo (1475-1564), influenced by the recommendations of their mentor – they were pleasantly surprised to discover works by the Flemish masters from the Baroque period in various museums and galleries they visited. ‘We were proud to see our fellow compatriots Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641)’.4 Inspired by their experiences in Roman art galleries, most students who stayed for a few years in Rome embarked on their own artistic endeavours, with the intention to send their works as envois back home for exhibitions in Paris or Brussels. Given the limited one-year duration of these three students' stay in Italy, most of their time was devoted to drawing inspiration from Italian masters, leaving the elaboration of their works for after their return to Brussels or Paris.

9

Albert Pierre Roberti,

A young Napolitan woman, n.d,

oil on canvas, 100 x 73 cm,

private collection

10

Albert Pierre Roberti,

The dancing tambourine player, n.d,

watercolour on paper, 26 x 17,5 cm,

location unknown

11

Albert Pierre Roberti,

The Tambourine Player, 1850,

oil on canvas, 94,5 x 79 cm,

private collection

12

Jules Storms

Couple in love, dated 1847

13

François-Joseph Navez,

Musical Group, 1821,

oil on canvas, 116,8 x 139,1 cm,

Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Mass., inv.no. 1976.1

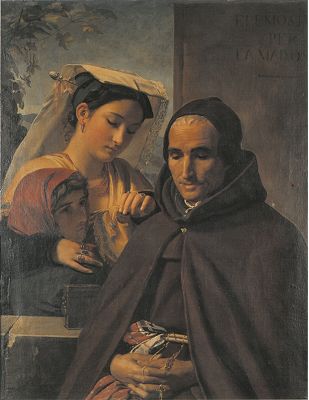

The post-Rome artworks of the students showcase a distinct emulation of Italian folk life, a popular theme in international painting.5 Scenes of musical performances with tambourines and traditional Italian costumes were particularly favoured by Navez’ students. [9-12] During their time in Rome, the triplet Van Eycken, Roberti and Storms often planned excursions to the Roman Campagna to capture the landscapes and local life in situ, while also escaping the summer heat. To support artists who couldn't sketch on site, prints of these costumes were distributed by for example Bartolomeo Pinelli (1781-1835) and Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778).6 In a letter to Navez, Roberti discusses the headgear of Italian women, inspiring works such as Tambourine Player (1850): ‘Women seldom wear hats; instead, they wear a white veil, somewhat resembling our shawls, which flatters the younger ones particularly well.’7 Similarly, Navez was enchanted by the Italian wardrobe during his travels, depicted in a number of his post-Italy period such as Musical Group and Hermit and two Young Girls [13-18].

14

François Joseph Navez

Hermit and two young girls, dated 1824

Private collection

15

François-Joseph Navez,

Neapolitan people, illegible date,

pencil on paper, 24,5 x 35,5 cm.

Musée des Beaux-Arts Charleroi, inv. no 318. Photo KIK-IRPA, Brussels

16

François-Joseph Navez,

The woman with the tambourine, 1827,

oil on panel, 122 x 175 cm,

Musée des Beaux-Arts Charleroi, inv. no. 122. Photo KIK-IRPA, Brussels

17

François Joseph Navez

Alms for the hermit, 1820

Whereabouts unknown

18

François Joseph Navez

Musical group, dated 1819

Notes

1 ‘Nous y avons découvert avec enthousiasme "F Navez 1819" le destinant que 20 ans plus tard vos élèves tracèrent leur nom sur ce même mur. Nous y trouvions aussi le nom du célèbre Gros.’ J.-B. Van Eycken and J. Storms to F.-J. Navez, Rome 15 October 1838, Manuscript Cabinet KBR, Ms. II 70/1/358, fol. 20r - 21r.

2 Anonymous s.d.

3 ‘Je ne quitte le Vatican que pour peindre d’après modèles qui sont ici de toute beauté. Voilà depuis un mois que nous faisons cela vu la saison des pluies; enfin, cher Maître, nous travaillons autant qu’il est possible. Le soir, nous dessinons à une académie que nous avons formée entre nous.’ A. Roberti to F.-J. Navez, Rome 15 December 1838, Manuscript Cabinet KBR, Ms. II 70/1/198, fol. 361r -361v.

4 J. Storms to F.-J. Navez, Florence 9 August 1838, Manuscript Cabinet KBR, Ms. II 70/1/269, fol. 485r -486r.

5 Roding 2003, pp. 43-45.

6 Roding 2003, pp. 42-43

7 ‘Les femmes portent rarement un chapeau: elles ont une voile blanc qui sont faits un peu comme nos failles et qui vont parfaitement bien aux jeunes.’ Coekelberghs/Jacobs/Loze 1999, p. 541.