Introduction

For centuries artists from the Low Countries were greatly attracted to the art and culture of Italy and Rome, 'the Eternal City', especially.1 This applied primarily to the remains of ancient civilization, the great art and architecture of the early modern period, and the landscape. Once a tradition of the artistic journey had been established, it gradually created an additional motive for travelling, prompting artists to join their – sometime famous - colleagues in Rome, capital of all art, from all over Europe and beyond. Finally, the rise of tourism and the expanding art market added economic incentives as well. The nineteenth century saw both the peak of this tradition of artists’ travels and its gradual decline [1-5].

The Prix de Rome (instituted in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1808), patrons, local funds or their own private means enabled many young Dutch and Belgian artists to travel to Italy for study and inspiration. Once arrived in Italy, they were obliged to find their own way. Obvious as this may seem for other parts of Italy, it was even true for Rome, where national Dutch or Belgian institutions in situ comparable to the French Academy (1666) were lacking for the greater part of this period. This resulted in a unique and distinctive sociability, rather different from the French art world in Rome, and not as numerous and less organized than the Deutschrömer.2

How did these artists from the Low Countries find their way, how did they cope? What did their professional and social lives look like? How did they relate to the artist communities of their Italian and foreign colleagues, and to the public and private institutions in the Roman cultural context? How did they shape their own identities as artists, Belgians (Flemish) and Dutchmen? How did they strike a balance between their new cosmopolitan and Italian homes and their countries of origin, whether they returned there or not? And how did they (re)define their positions in light of not just the artistic, but also the social, economic and political transformations they witnessed?

The (art) historical interest in the presence of Belgian and Dutch artists in nineteenth-century Italy arose at the time of the establishment of the foreign historical institutes in Rome: the Belgian Historical Institute and the Princess Marie José Foundation (1902), the Dutch Historical Institute (1904), later the (Royal) Netherlands Institute in Rome (K)NIR and the Accademia Belgica, and finally the Dutch Art History Institute in Florence (1958), now NIKI.3 Since then, this area of interest has remained part of the research and publications of these institutes, and it is therefore only fitting that the new perspectives within this field of research proposed here, found their origins with a workshop hosted by these two institutions.

During the 1970s and 1980s especially, Belgian and Dutch art historians conducted important new research on artists from the Low Countries working in Italy.4 While these studies remain valuable, they primarily focused on formal aspects and paid less attention to the transnational cultural, social, and political contexts in which these artists lived and worked. Similar observations apply to art historical research on nineteenth-century artists from other countries up to the 1990s, albeit with some notable exceptions.5

In recent decades, international scholarship has increasingly sought to address these gaps for Italian and foreign artist, focusing first and foremost on the city of Rome as a cosmopolitan ‘Universal and Eternal Capital of Arts’. As the reference between quotation marks shows, a landmark of this new wave of scholarship were the exhibitions and publications under the title Maestà di Roma (2003). Their initiators, and especially their followers have ever since carried the flame of transnational art and cultural historical research into the artists community in Rome, with innovative studies and methods.6

Comparable efforts concerning artists from the Low Countries in recent decades have however been scarce, though not entirely lacking.7 This publication aims to bridge the divide outlined here, by bringing together scholars from Belgium and the Netherlands who have helped pave the way for new research already some years ago, and those who have made more recent contributions to the field.8 With their joint efforts, this RKD Study tries to reconnect the study of Belgian and Dutch nineteenth-century artists in Italy with recent developments in art historical research on the presence of foreign artists in nineteenth-century Italy in particular, and current trends in global (art) historical research in general. May it be seen as an invitation to many other colleagues to continue on the paths proposed here.

1

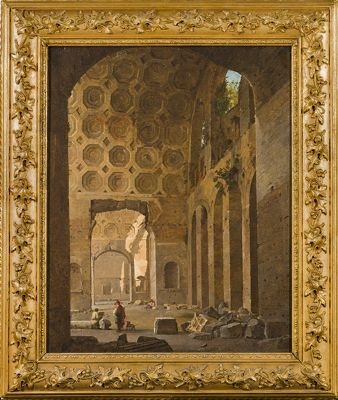

Cornelis Kruseman Frans Vervloet Jean Baptiste Lodewijk Maes Canini

View on the ruins of the Basilica of Maxentius in Rome, dated 1823

The Hague, Cornelis Kruseman - J.M.C. Ising Stichting

2

Frans Vervloet

Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Rome, dated 1864

Whereabouts unknown

3

Abraham Teerlink

The waterfalls of Tivoli with a nearing thunderstorm, 1824 (dated)

Rome, Istituto Storico Olandese

4

Pierre Louis Dubourcq

Landscape near Rome, 1843-1844

Amsterdam, Amsterdam Museum, inv./cat.nr. SA 1934

5

Eugène Simonis,

The Unhappy Toddler / The Broken Drum / The Child with the Drum, 1842,

plaster, 47 x 83 x 40.5 cm,

Royal Museums of Fine Art of Belgium, Brussels, inv. no. 3136

Notes

1 The bibliographical references provided in this introduction are by no means exhaustive. For a comprehensive bibliography, please refer to the search strings in the catalogue of the RKD library, and the bibliography of the chapters in this RKD Study.

2 Deutschrömer are the German visual artists and writers living in Rome, especially in the late 18th and 19th century.

3 In the case of the Netherlands, the work of G.J. Hoogewerff from the 1920s must be mentioned, e.g. his article 'Nederlandsche kunstenaars te Rome in de XIXe eeuw', Mededeelingen van het Nederlandsch Historisch Instituut te Rome 13 (1933), pp. 147-196. In roughly the same period the groundbreaking inventory by the German journalist and art historian Friedrich Noack (1858–1930) was published, in which Dutch and Flemish artists are counted as ‘German’ see F. Noack, Das Deutschtum in Rom seit dem Ausgang des Mittelalters, (2 vol.), Stuttgart 1927. Noacks systematic card index, which is kept in the Bibliotheca Hertziana archive, was digitised in 2006 and indexed by artist name. It comprises over 18,000 handwritten cards (mostly in old shorthand, Gabelsberger system) with over 11,000 entries on artists working in Rome (including archive excerpts, newspaper articles, etc.), see https://db.biblhertz.it/noack/noack.xml.

4 At least the following titles should be mentioned: D. Coekelberghs, Les peintres Belges à Rome de 1700 à 1830, Brussel 1976; E. Bergvelt et al., Reizen naar Rome. Italië als leerschool voor Nederlandse kunstenaars omstreeks 1800 / Paesaggisti ed altri artisti olandesi a Roma intorno al 1800, tent.cat. Haarlem (Teylers Museum) / Rome (Nederlands Instituut Rome) 1984; R. van Leeuwen, Kopiëren in Florence : kunstenaars uit de Lage Landen in Toscane en de 19de-eeuwse kunstreis naar Italië, Florence 1985.

5 E.g. U. Peters et al., Das Künstlerleben in Rom. Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844): der dänische Bildhauer und seine deutschen Freunde, Nürnberg 1991.

6 Two exhibitions and two catalogues under the title Maestà di Roma were realised, one subtitled D’Ingres à Dégas. Les artistes français à Rome (…), the other Universale ed Eterna Capitale delle Arti. The latter did not come out of nowhere. Its curators and initiators, to whom Stefano Susinno (1945-2002) should be added in mind, already had a long track record in this line of research. Among their pupils and followers, at least Giovanna Capitelli, Carla Mazzarelli, Matteo Lafranconi, Serenella Rolfi Ozvald and Stefano Grandesso should be mentioned. Among their publications: G. Capitelli et al., Roma fuori di Roma. L’esportazione dell’arte moderna da Pio VI all’ Unità 1775-1870, Rome 2012; G. Capitelli et al., Roma en México : México en Roma : las academias de arte entre Europa y en Nuevo Mundo 1843-1867, Rome 2018; C. Mazzarelli, Dipingere in copia : da Roma all'Europa, 1750-1870, Rome 2018; Another important later and indirect result of Maestà was O. Bonfait (ed.), Le peuple de Rome : représentations et imaginaire de Napoléon à l'unité italienne, Montreuil/Ajaccio 2013.

7 An example of such an effort was the insightful exhibition De blijvende verlokking : kunstenaars uit de Lage Landen in Italië 1806-1940, held from March to August 2003 at the Kunsthal in Rotterdam and the accompanying catalogue: D. Adelaar, M. Roding and B. Tempel, De blijvende verlokking. Kunstenaars uit de Lage Landen in Italië 1806-1940, Schiedam 2003 .

8 See e.g. C.A. Dupont, Modèles italiens et traditions nationales. Les artistes belges en Italie (1830-1914), 2 dln., Brussels/Rome 2005, J. Ph. Koelman, In Rome 1846-1851, ed. A. Pelgrom with afterword and biographical register, Rome 2023 and E. Geudeker, Cornelis Kruseman (1797-1857). Aardse roem en hemelse ambitie, The Hague 2024.